Surveys of Fruit Bats in Miag-ao

2021

Miag-ao is a municipality in the Province of Iloilo with 119 barangays and according to the 2020 census, it has a total population of 68,115. It is a first-class municipality and has very rich historical stories to tell…

The most famous of course, is the Miag-ao Santo Tomas de Villanueva Church. According to Vito (2015), it was constructed through forced labour from 1787 and was completed after ten years (1797) during the Spanish occupation. Because of the artistic sculptural relief carved on its facade and its history, it was declared as a UNESCO World Heritage Site on December 11, 1993.

The images above are the side (Photo by Norielle Diamante) and the front side (Photo by Norman Posecion) of Miag-ao Church.

According to Matias (2017), Another spectacular architecture that can be found in the Municipality of Miag-ao is the Britanico Bridge, formerly Sapa Bridge. It is a stone bridge built using coral bricks from the quarries of the adjacent town of San Joaquin during the Spanish era in 1873. The locals claimed that the bridge is home to mythical creatures like the White Lady and many more. But those stories only made the bridge more fascinating and authentic. It is located beside Sulu Garden, which was a bakery before the restaurant was constructed.

Britanico Bridge also known as Sapa Bridge beside Sulu Garden Restaurant (Left: Photo by Norielle Diamante and right: Photo by Nick Foster).

Britanico Bridge also known as Sapa Bridge beside Sulu Garden Restaurant (Left: Photo by Norielle Diamante and right: Photo by Nick Foster).

These and more historical structures will capture your attention when you visit the municipality of Miag-ao. But nothing is more amazing than the tourist attractions brought about by nature itself – the FRUIT BATS.

Just after you arrive at the center of the municipality, you will notice the strong smell of bat urine, not to mention the screeching sounds these bats make. But give it at least ten minutes, and you’ll just get used to the smell, like what the locals have become after decades of coexisting with bats in Miag-ao.

You will see that most of the Agoho (Casuarina. Equisetifolia) trees and one Narra (Pterocarpus indicus) tree at the right side of Miag-ao Church have become the roosting sites of the Common Island Flying Fox (Pteropus hypomelanus), the smallest species of its genus. That and of more trees within the Poblacion area. They belong to the Old World Fruit Bats, the kind of bats that has the ability to see clearly and does not rely on echolocation to hunt for food.

P. Hypomelanus is geographically found in the Indo-Australian region, including the Philippines, Solomon Islands, and Papua New Guinea. Their body is fully furred and a noticeable golden dorsal part makes it easy to identify the Common Island Flying Fox from other species of bats, according to Ouilette (2006). This species is included in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which according to the Department of Environment and Natural Resources Administrative Order (DAO) 2019-09 is considered to be an Endangered species.

(Image on the right) Close-up shot of Common Island Flying Fox roosting showing its golden dorsal.

These bats have been coexisting with the people of Miag-ao for more than 70 years, according to the residents living within the area. In the year 2014 (Matias), the bat population was counted to about 5,000 individuals and more than 7,000 (Matias, 2016) individuals before they transferred from the Bubog tree (Sterculia foetida) that they used to roost last 2018. They abandoned the tree after it “died”, but the tree now seems to recover three years later.

The Bubog tree (left) where the Common Island Flying Foxes used to roost. New leaves can now be seen sprouting again from the tree.

READ MORE about fruit bats & the Bubog tree >>>

Map of Fruit Bats in Miag-ao

How to use our interactive map

Display Bat Information – Select the bat icon and click it to display more information.

Zoom Map – Scroll your mouse to zoom in the map to view the detailed objects.

Change Map View – Press and hold the left mouse button and drag it in any direction within the map to change map view.

LEGEND:

![]() The bat icons represent the trees where the Common Island Flying Fox roost.

The bat icons represent the trees where the Common Island Flying Fox roost.

![]() Government/Civil Building

Government/Civil Building

![]() Historic Building/Place

Historic Building/Place

![]() Monument/Public Plaza

Monument/Public Plaza

![]() Market/Shopping Center

Market/Shopping Center

Bat survey was conducted last September 2021 and is scheduled every 4 months. The next survey will be in January 2022.

Population Survey of Miag-ao’s Fruit Bats

From the period of August 26 to September 3, 2021, the staff from Sulu Garden Foundation surveyed the Municipality of Miag-ao to list, identify and plot the roosting sites of Common Island Foxes on a map and count their population.

Visual count was used and the count started as early as 6 A.M. and as late as 4 P.M., as the bats are still roosting. Each tree was counted three times to get the average count and the standard error per tree were calculated to make sure that the count is as near accurate as possible. Those with more than 10% standard error were recounted. Each tree was identified to their species level and rated to the condition of the damage that the bats have caused while roosting.

There are 46 individual trees recorded as the bats’ roosting sites and it consists of 14 species.

The 14 species of trees are: Agoho (Casuarina equisetifolia), Narra (Pterocarpus indicus), Mango (Mangifera indica), Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla), Coconut (Cocos nucifera), Caimito (Chrysophyllum cainito), Santol (Sandoricum koetjape), Lanete (Wrightia pubescens), Sambag (Tamarindus indica), Acacia (Samanea saman), Lunok (Ficus), Gmelina (Gmelina arborea), Kamansi (Artocarpus camansi), and Duldol (Ceiba pentandra)

Three (3) of the tree species, namely: Narra (Vulnerable based on DAO 2017-11), Acacia and Lanete are listed in the Philippine Premium Tree Species based on DAO 78-87 and Mahogany is considered Endangered based on DAO 2017-11, since it is listed under Appendix II in CITES. That means these trees are protected by the law.

The Common Island Flying Foxes’ average total population in the town of Miag-ao is 7,392 individuals as of September 3, 2021. The highest count in a tree was from the Acacia tree with 1,044±4 individuals and the least was from the 2 Agoho trees beside Miag-ao Church with only 3 counts each.

Table 1. Distribution of the Bat Population among different trees around Miag-ao town plaza.

| TREE # | TREE SPECIES | TREE CONDITION RATING* | COUNT | NUMBER OF BATS (MEAN ± SEM) | ||

| 1st COUNT | 2nd COUNT | 3rd COUNT | ||||

| 1 | Agoho (Casuarina equisetifolia) | 5 | 28 | 25 | 25 | 26 ± 1 |

| 2 | Agoho (Casuarina equisetifolia) | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 3 | Agoho (Casuarina equisetifolia) | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | Agoho (Casuarina equisetifolia) | 5 | 65 | 90 | 74 | 76 ± 7 |

| 5 | Agoho (Casuarina equisetifolia) | 5 | 75 | 65 | 69 | 69 ± 3 |

| 6 | Agoho (Casuarina equisetifolia) | 5 | 153 | 155 | 155 | 154 ± 1 |

| 7 | Agoho (Casuarina equisetifolia) | 5 | 130 | 132 | 130 | 131 ± 1 |

| 8 | Agoho (Casuarina equisetifolia) | 5 | 120 | 132 | 136 | 129 ± 5 |

| 9 | Agoho (Casuarina equisetifolia) | 5 | 149 | 152 | 150 | 150 ± 1 |

| 10 | Agoho (Casuarina equisetifolia) | 5 | 124 | 129 | 129 | 127 ± 2 |

| 11 | Agoho (Casuarina equisetifolia) | 5 | 117 | 115 | 117 | 116 ± 1 |

| 12 | Narra (Pterocarpus indicus) | 5 | 250 | 250 | 251 | 250 |

| 13 | Agoho (Casuarina equisetifolia) | 4 | 154 | 160 | 158 | 157 ± 2 |

| 14 | Agoho (Casuarina equisetifolia) | 4 | 197 | 208 | 202 | 202 ± 3 |

| 15 | Indian Mango (Mangifera indica) | 5 | 237 | 259 | 247 | 248 ± 6 |

| 16 | Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) | 5 | 41 | 52 | 49 | 47 ± 3 |

| 17 | Coconut (Cocos nucifera) | 4 | 32 | 35 | 35 | 34 ± 1 |

| 18 | Coconut (Cocos nucifera) | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 19 | Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) | 3 | 228 | 233 | 221 | 227 ± 3 |

| 20 | Caimito (Chrysophyllum cainito) | 2 | 35 | 33 | 34 | 34 ± 1 |

| 21 | Santol (Sandoricum koetjape) | 3 | 132 | 135 | 129 | 132 ± 2 |

| 22 | Caimito (Chrysophyllum cainito) | 5 | 17 | 26 | 24 | 22 ± 3 |

| 23 | Lanete (Wrightia pubescens) | 5 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 15 |

| 24 | Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) | 4 | 291 | 296 | 287 | 291 ± 3 |

| 25 | Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) | 3 | 235 | 250 | 238 | 241 ± 5 |

| 26 | Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) | 5 | 125 | 130 | 132 | 129 ± 2 |

| 27 | Coconut (Cocos nucifera) | 4 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 28 | Caimito (Chrysophyllum cainito) | 5 | 81 | 79 | 87 | 82 ± 2 |

| 29 | Indian Mango (Mangifera indica) | 3 | 480 | 495 | 489 | 488 ± 4 |

| 30 | Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) | 5 | 156 | 159 | 160 | 158 ± 1 |

| 31 | Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) | 3 | 113 | 130 | 118 | 120 ± 5 |

| 32 | Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) | 5 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 33 | Narra (Pterocarpus indicus) | 2 | 291 | 314 | 302 | 304 ± 7 |

| 34 | Caimito (Chrysophyllum cainito) | 1 | 146 | 149 | 152 | 149 ± 2 |

| 35 | Sambag (Tamarindus indica) | 3 | 205 | 213 | 209 | 209 ± 2 |

| 36 | Acacia (Samanea saman) | 1 | 977 | 983 | 985 | 982 ± 2 |

| 37 | Lunok (Ficus sp.) | 4 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| 38 | Acacia (Samanea saman) | 2 | 1050 | 1045 | 1036 | 1044 ± 4 |

| 39 | Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) | 4 | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 |

| 40 | Gmelina (Gmelina arborea) | 5 | 57 | 63 | 67 | 62 ± 3 |

| 41 | Gmelina (Gmelina arborea) | 4 | 27 | 30 | 30 | 29 ± 1 |

| 42 | Mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla) | 3 | 309 | 311 | 300 | 307 ± 3 |

| 43 | Indian Mango (Mangifera odorata) | 3 | 118 | 128 | 125 | 124 ± 3 |

| 44 | Kamansi (Artocarpus camansi) | 4 | 73 | 77 | 68 | 73 ± 3 |

| 45 | Duldol (Ceiba pentandra) | 4 | 44 | 48 | 39 | 44 ± 3 |

| 46 | Acacia (Samanea saman) | 3 | 145 | 132 | 151 | 153 ± 6 |

*Rating of the damage to the trees: 1 = 81% – 100% damage 2 = 61% – 80% damage 3 = 41% – 60% damage 4 = 21% – 40% damage 5 = 0% – 20% damage

Thirteen (13) out of the 46 roosting trees of the Common Island Flying Fox are Agoho; followed by 10 Mahogany; 4 Caimito; 3 Mango and Coconut; 2 Acacia, Narra and Gmelina; and 1 for the remaining six species of trees.

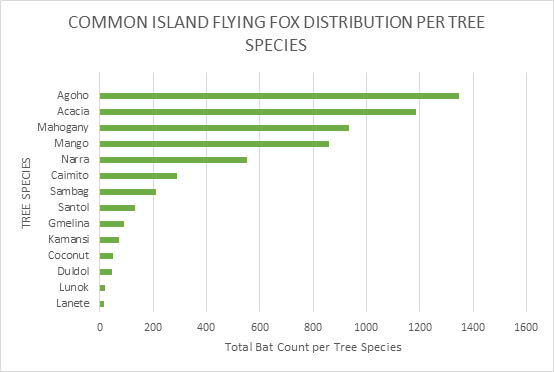

The highest total average count per tree species is of Agoho tree with 1,346 individuals, followed by the Acacia tree with 1,186 bats, Mahogany tree with 936 bats, Mango tree with 859 bats, Narra tree with 553 bats, Caimito tree with 288 bats, Sambag tree with 209 bats, Santol tree with 132 bats, Gmelina with 91 bats, Kamansi with 73 bats, Coconut with 49, Duldol with 44, Lunok with 19, and Lanete with 15 bats.

Figure 1. Bar chart showing the total average population of the Common Island Flying Fox per tree species (survey date, September 2021)

Bat Counts in 2016 and 2021

Fruit bat population count in 2016 was conducted through a video capture as the bats were flying out of the Bubog tree towards the mountains of Antique Province, between 2014-2016. Because of the high density of bats in that single tree, it was deemed impossible to accurately do a manual count. The total count in 2016 was 7,604. Five years later, the fruit bat population was surveyed again using a manual count of each bat in each tree during the day when they are resting. The visual counts were conducted by three (3) different researchers for each tree in September of 2021. The total population count yielded 7,392 fruit bats (see figure and table above). Assuming that the 2016 count was as reliable, the numbers seem to not make sense. The population did not grow beyond the 7,000+ range. This might be due to many reasons:

- There might be a high attrition rate as the bats dispersed to other trees. Increased death rates or low birth rates might be one of the causes. Often, residents living near the bat trees observed many dead and dying bats on the ground, particularly during the hot summer months of March to June.

- It might also be possible that not all the bats from the original Bubog tree settled in Miag-ao. Many others might have resettled on more favourable trees and locations outside town.

Bat Overpopulation

Since fruit bats play a vital role in the pollination of fruit trees, they are protected by the government. They are conserved since their population worldwide is declining. The roosting trees tend to die due to overcrowding of the bats on the branches, and probably due to the high urine concentration that they excrete. In Australia, the presence of Little Red Flying-Fox tends to provoke more public angst because of their typically large numbers and tree-damaging dense roosting habits (Edson, et. al., 2015). Take, for example, the Bubog Tree that they used to roost behind the Miag-ao Municipal Hall. The bats crowded in that one tree before, and after it lost all its leaves and seemed to die, all the bats relocated and left the tree bare. Fortunately, the tree seems to recover now.

Fruit bats feed on native fruits, such as figs. Overpopulation expands their foraging range and they start feeding on commercially important fruits, such as mangos and bananas, causing economic losses to farmers. In the island of Mauritius, located east of Madagascar, 50,000 fruit bats were killed to reduce the population to less than 30,000 and prevent the economic losses of fruit farmers.

Bats as Virus Reservoir Host

Based on the final report released by the World Health Organization (WHO) and China on the origins of SARS-CoV-2 (Joint WHO-China Study, 2020), the SARS-CoV-2 genome has 96.2% similarity to a bat SARS-related coronavirus. In Cambodia, two Rhinolopus shameli bats were sampled and their viruses’ overall nucleotide identity shared 92.6% with SARS-CoV-2. A study of Rhinolopus acuminatus bats in Thailand also showed near-identical viruses in five animals from a single colony.

Hendra virus (HeV) as seen at the left is a bat-borne virus that is associated with a highly fatal infection in horses and humans. Numerous disease outbreaks in Australia among horses have been caused by Hendra virus. (Image Source: https://www.news-medical.net/news/20110516/Hendra-virus-vaccine-to-be-released-soon.aspx)

According to Janicki & Scarr (2021), this is not the first time that bats are suspected of being the host of viruses that also caused outbreaks before. The Ebola and Nipah viruses were found to come from bats. They harbour more viruses per species and since they are known to fly long distances, there’s a big possibility of them carrying these viruses, usually transferring to blood-sucking vectors and passed on to vulnerable hosts, most especially, humans.

Bats of the genus Pteropus, commonly known as flying foxes, are the natural host of Hendra virus (HeV), a novel paramyxovirus that periodically causes fatal disease in Australia. (Edson, et. al., 2015).

There are 80 species of viruses detected from bats as of date. One of them is the Rift Valley Fever Virus (RVFV) which was identified in Kenya in 1930. The largest outbreak occurred in Egypt in 1977-1978 with an estimated 200,000 human infections, 18,000 cases of illness and 600 deaths. The clinical symptoms are flu-like fever, muscle pain or headache to neck stiffness, retinal lesions, loss of memory and even death. However, humans are not the only ones affected by this virus, but livestock as well, resulting in devastating economic losses (Busch, et. al., 2013).

Conservation and Health

Despite all the health risks on people and other animals, we cannot deny the fact that fruit bats are very important to our environment. They are major pollinators of fruit trees. However, because of the viruses and other pathogenic microorganisms that they host, we should also keep our distance away from them. Eating bat meat is not safe when there are a lot of zoonotic diseases that have yet to be discovered. Some people still hunt bats as a delicacy. Other predators of bats are pythons, monitor lizards and even dogs. Viruses may jump from bats to these predators and then to people. Proper handling of livestock and domesticated animals should be done to keep them from acquiring viruses and diseases from bats and transferring them to humans and other animals.

What’s Next?

The Common Island Flying Fox research is an ongoing scientific study being conducted by the research staff of Sulu Garden Foundation. Bat population count and monitoring will be conducted regularly to create baseline data to assist local and national governments in the conservation and prevention of diseases that may originate from the bats of Miag-ao.

The world is already feeling the devastation of the Covid-19 pandemic caused by the Wuhan Coronavirus, which likely originated from bats. This pandemic has already ruined the city of Wuhan’s reputation and heritage for decades to come. We should take extreme precautions that the next viral disease outbreak should not have the name Miag-ao Virus attached to it.

References:

- Vito, J. (2015). Miagao Church: UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Happy Trip.

- Matias, J. R. (September 25, 2017). Puente de Britanico. Miagao History.

- Ouillette, R. (2006). Pteropus hypomelanus. Animal Diversity Web.

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). (Valid from June 22, 2021). Appendices I, II and III.

- Department of Environment and Natural Resource (DENR). (July 12, 2019). Updated National List of Threatened Philippine Fauna and their Categories. DENR Administrative Order (DAO) No. 2019-09.

- Department of Environment and Natural Resource (DENR). (May 2, 2017). Updated National List of Threatened Philippine Plants and their Categories. DENR Administrative Order (DAO) No. 2017-11.

- Department of Environment and Natural Resource (DENR). (December 28, 1987). Interim Guidelines on the Cutting/Gathering of Narra and Other Premium Hardwood Species. DENR Administrative Order (DAO) No. 78.

- Matias, J. R., et al. (2016). Bats of Miagao. Part 1. Sulu Garden.

- Matias, J. (May 20, 2014). The Bats of Miagao. Sulu Garden.

- Aylward, B., et al. (February 24, 2020). Report of the WHO-China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). WHO-China Joint Mission.

- Janicki, J. & Scarr, S. (March 2, 2021). Bats and the Origin of Outbreaks. Reuters Graphics.

- Busch, M. W., et al. (September 2013). Bats as Potential Reservoir Hosts fo Vector-Borne Diseases.

- Edson, D., et al. (May 27, 2015). Flying-Fox Roost Disturbance and Hendra Virus Spillover Risk. PLoS ONE 10.

- Mandal, A. (May 16, 2021). Hendra Virus Vaccine to be Released Soon. News Medical Life Sciences.

- Nuwer. R. (March 1, 2019). These Endangered Bats are Being Killed by the Thousands—Here’s Why. National Geographic.

Written by: Senior Science Officer, Norielle Diamante (See profile)